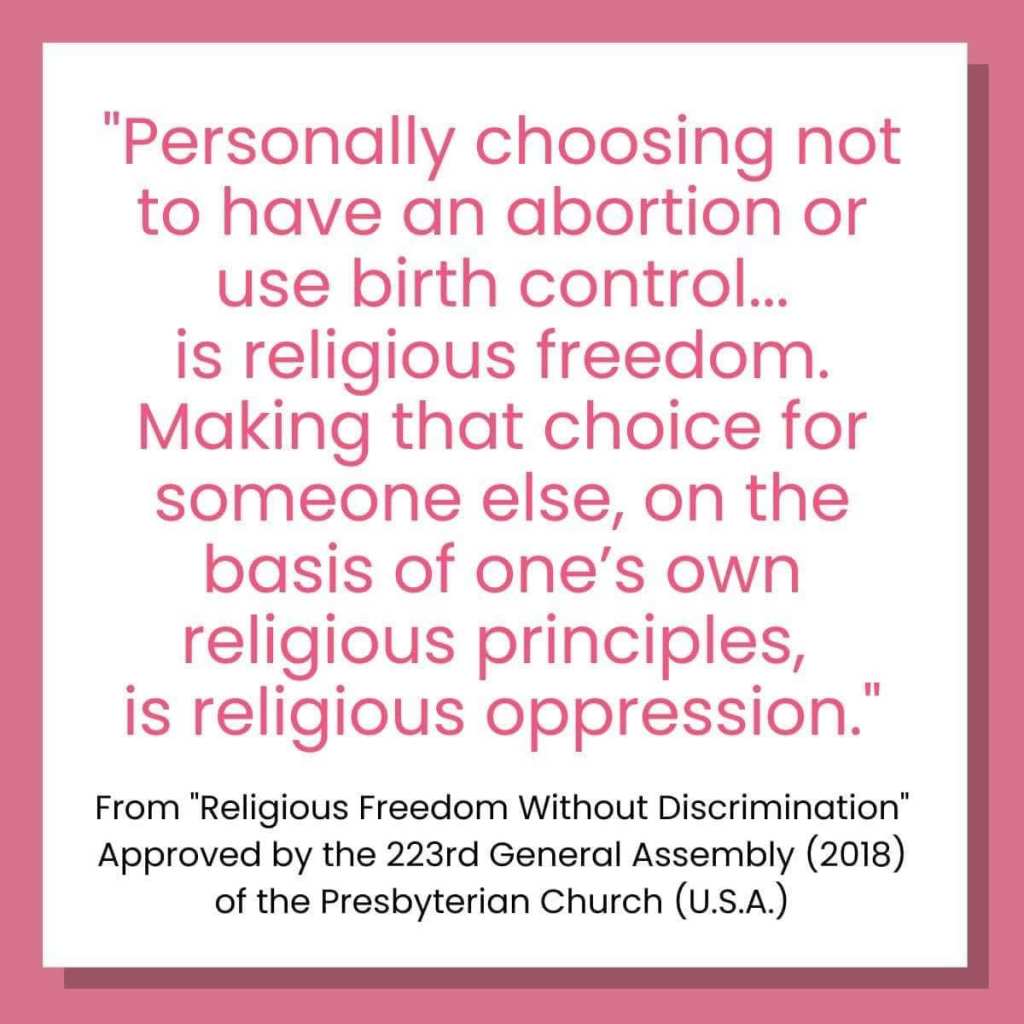

While Christians in the United States have a reputation for being pro-life, Christians are, like many groups, divided on the question of abortion. Following the leaked Supreme Court draft decision on Roe v. Wade, my social networks exploded with Christian memes in favor of abortion, like the excerpt of the 2018 Presbyterian USA statement “Religious Freedom without Discrimination.”

Christianity has been so thoroughly linked to the pro-life movement that it can be confusing how Christians got from here to there. Christians who support abortion on the grounds of about bodily autonomy, feminism, forgiveness, social safety nets, or science can sound more like liberal talking points than claims about who God is and what God hopes for humanity. However, these beliefs are rooted in a coherent and deeply Christian theology. It’s called incarnational, or embodied, theology.

Christians who defend abortion hold a fundamental assumption about who God is: flesh incarnate. God chose to come to earth in a human body because human bodies are inherently good, and holy, and at times a little bit silly. With the birth of Jesus, God made the stunning claim that the world directly in front of us is as holy as the place where God dwells. To have a body is to be loved by God, even if your body is awkward or doesn’t work very well or comes with a uterus or has chronic illness or is a child. In short: Jesus’ arrival on earth was an affirmation that every body is a beach body.

For pro-abortion Christians, this view of Jesus leads to two other beliefs: (1) sex is not sinful and, in fact, is an inherently holy reminder of human dignity and (2) life and death are blurry categories that are both holy. These views come directly from the Gospels. The first is about Jesus’ birth, and the second is about Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Through the birth of Jesus, God chose the human body as the means for salvation. God reiterated the Genesis claim that humans were created good, bodies and all. Bodies are good not because some intangible divinity (the soul) temporarily resides there, but because the body is where intangible divinity meets concrete matter. Where stuff meets not-stuff. This means that everything bodies do—get fat, get old, get pregnant, snore, poop, make silly noises, have sex—is good and is sacred. Sex does not need to be controlled or punished, but should be approached as a holy gift from God. Because this theology has low anxiety about sex, these Christians also have minimal desire to control the outcome of sex. Sex can result in a multitude of outcomes, from no pregnancy to miscarriage to full-term birth to termination of pregnancy, and all of these are natural and honor the diversity of what it means to have a holy body. In spite of, or perhaps because, Jesus’ conception did not involve sex in our traditional sense, incarnational theology calls for a more expansive and embodied theology of sex. It is the fact of God-made-flesh that makes the body and all it does holy, not the details of Jesus’ conception. Likewise, this claim about the divinity of the body, created and nurtured inside a woman, counters the reading of Genesis that because woman was made from man’s rib she is inferior to man (and therefore should be controlled by men). Body is a body is a body, and all of it is what God called good.

![A quote from Raphael Warnock: "For me, reproductive justice is consistent with my commitment to [ensuring health care as a human right]. I believe unequivocally in a woman's right to choose."](https://gatheringthestones.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/rev-raphael-warnock.jpg?w=300)

At the other end of Jesus’ life, an incarnational reading views the death and resurrection as a redemption that blurs our traditional concept of “death = bad, life = good.” God empowered us not to fear death. Just as Jesus became flesh to walk alongside humanity, God stays near to humanity in death. This counters the “life-at-all-costs” ethic that runs deep in both Christian and American society. Jesus’ death teaches us that it is possible to die well, to die as a result of living in impossible and unjust systems, and to still be connected to God. Jesus’ resurrection, alongside the raising of Lazarus and others, also tells us that the line between life and death is blurry. There is a certain humility required of us in the liminal spaces, whether at the end of the lifespan or the beginning. This is why Christians are hesitant to assume that the fusion of sperm and egg equates to a baby—having a body is anything but clear-cut.

A consistent incarnational theology results in not just greater openness to abortion but also to end-of-life care, such as being removed from a ventilator when the brain has stopped functioning. These liminal states are not binaries, not “life vs. death” or “good vs. bad”—they simply are part of the incarnational experience. God-made-flesh is a repudiation of binaries.

Although Christians today are known as pro-life zealots, that is a relatively recent phenomenon (with a fraught history). The Christian theology of abortion is deeply nuanced. Pro-abortion Christians exist because of Christ, not politics.