In the wake of Charlottesville, the Internet can be divided into two (three) people: the people crying that we should all “love our enemy;” the people shouting “They are literally trying to kill me;” (and the neo-Nazi defenders, who promote killing the aforementioned people; don’t even go down that rabbit hole).

The crux of the argument between the first two groups: Can You Love the Enemy who is Trying to Kill You?

Can You Love the Enemy Who is Trying to Kill You?

Spoiler Alert: if you’re Christian, you have to find a way from here to there. Jesus himself says the problematic phrase “Love your enemies.” But there are some twists and turns before we get there.

The problem with the enemy-loving question, especially on the Internet, is that most people argue from a Kantian perspective. To be perfectly objective, Immanuel Kant is a German philosopher who tried to universalize his own privilege as a mechanism for ethical discernment. Those calling for enemy-loving are often trying to universalize a moral claim in order to apply it to someone else. More pointedly, they tend to be privileged people suggesting that because I am white and I have been your enemy, you must love me. People who have done wrong have a vested interest in convincing the wronged to love their enemies. This is why Kant is insufficient.

Taking Kant out of the equation, we have two other starting points.

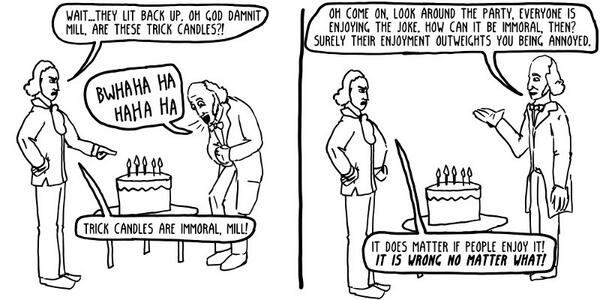

John Stuart Mill at Kant’s Birthday (from Existential Comics).

First, all ethics is situational ethics. Ethics is shaped and defined by the situation in which it occurs. The Bible is full of ethics that only apply because of the unique situation (it is a highly specific situation when Jacob is applauded for wrestling an angel). Second, morality can be Role-Based. The moral response depends on the role you play in the situation. Different roles carry different amounts of power, and what’s morally conscionable shifts depending how much power you have. As Karen Lebascqz writes, “power that attaches to [one’s] role is morally relevant in determining an appropriate… ethic.” This is the Robin Hood premise–we defend Robin Hood’s morality because he steals from the wealthy to feed the starving.

Understanding situational ethics and role-based morality, we have a more nuanced answer to the question Can You Love the Enemy Who is Trying to Kill You? There are two definitions of kill and three definitions of love that allow us to say “yes.”

The two definitions of kill:

1) the actual violence of an individual or group that gives a person reasonable suspicion of harm

2) the figurative language of historical memory, recalling a time when violence up-to-and-including-death was routinely perpetrated by one group against another

(1) Many people of color and Jews have expressed this post-Charlottesville in their own fears and in their calls for better allyship. If you’re struggling with this one, check your own privilege and educate yourself.

(2) People in power often want to ignore this definition because it means that sometimes, when people are mad at you, their anger is justified. “Kill” does not always literally mean “kill,” but it is the certain knowledge that a person–even a professed ally–could kill you at any time without repercussions, and that is never not part of your relationship to the ally.

Too often in social discourse, the privileged try to set the terms of enemy-loving. But you lost the right do that when you (or your predecessors) persecuted an entire group.

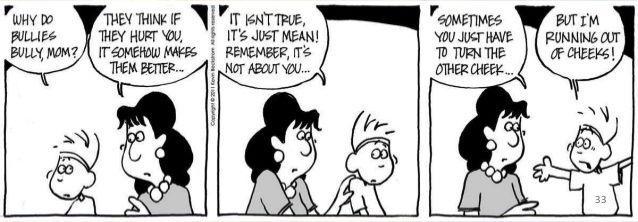

How white people sound sometimes when they say “Love Your Enemy.”

White people cannot demand that people of color love them because they are enemies (racism still exists). Men cannot demand that women love them because they are enemies (see Taylor Swift testimony). Heterosexuals cannot demand that gay people love them because they are enemies (the church can’t be sorry gay people are sad while it’s discriminating against gay people). To return to situational ethics: I sometimes behave what-would-otherwise-be rudely to men out of the historical memory and sense of risk I have being around men. But because I am white, people of color may also behave what-would-otherwise-be rudely to me. “Rudeness” shifts with power. I cannot call another person “rude” if they are concerned for their basic survival and preservation of humanity. Trust is earned and interpersonal, and part of earning trust is not policing the behavior of survivors. If you are on the Internet calling us to “all get along,” consider whether you are saying (or others are hearing you say) “love me because I have wronged you.”

The three definitions of love:

1) a commitment to the nurture, thriving, and growth [of an enemy]

2) from the complicated philosopher Taylor Swift, who declares “like any great love, it keeps you guessing/like any real love, it’s ever-changing/like any true love, it drives you crazy”

3) Karen Lebacqz’s practice of enemy-loving as the dance between “forgiveness and survival”

This allows us to rephrase the question:

(1) Can You Commit to the Nurture, Thriving, and Growth of an Enemy Who is Trying to (Literally) Kill You?

There are a number of social justice warriors who model this: Martin Luther King, Jr; Ghandi; Oscar Romero; Elizabeth Cady Stanton; Jesus. Jesus loves his enemies in a strategic, disruptive, threateningly nonviolent way that that supports the nurture, thriving, and growth of his enemies. He confronts enemies who have both more and less power than him: he welcomes Zacchaeus down from a lonely and uncomfortable tree; he befriends a Samaritan woman; he preaches justice. Sometimes, his body at risk. But he takes calculated risks to shift the conditions and social environment, impacting partial-allies who can influence enemies. Can you facilitate the nurture, thriving, and growth of neo-Nazis?

(2) Can You Respond to the Enemy Who is Trying to (Literally) Kill You and Keep Them Guessing, Ever-changing, and Drive them Crazy?

Since I first heard “Welcome to New York,” I’ve valued T. Swift’s description of real, true, and great love. It’s a divine description, a love that keeps you guessing, ever-changing, and driving you crazy. Jesus kept his enemies guessing: if he was not going to start a violent rebellion, what would he do? Through strategic dialogues in spaces where he had a probability of safety, Jesus provoked change. When people were unwilling to change, he forced them to confront and confess that they were not changing. In the underhanded way the institutions tried-and-failed to stop him, he drove them crazy. Can you keep neo-Nazis guessing, ever-changing, and drive them crazy?

(3) Can You Forgive and Survive the Enemy Who Has Historically Tried to Kill You?

This definition does not apply to the men (and women) rallying in Charlottesville as much as it does the so-called allies whose response has been lackluster. It applies to the practice of intimate enemy-love, people struggling to come to terms with the fact that because of historical memory or actual repeated microaggression they are your enemy.

Karen Lebacqz argues that feminists in heterosexual relationships are practicing love of enemy. She describes the two guiding principles in these relationships as Forgiveness and Survival. You can extend forgiveness if and only if the enemy recognizes that they need pardoning (which is why this form of love applies to allies, not neo-Nazis). Forgiveness is an enemy-loving practice. But forgiveness is never the culmination of the relationship–the culmination is survival. Thus, Eliza Hamilton can “take [her husband’s] hand” and declare that “it’s quiet uptown” while she simultaneously says “you forfeit all right to my bed/you’ll sleep in your office instead.” Her forgiveness is woven into survival.

There is a difference between survival and revenge. Survival is the first definition of love–the desire for your own nurture, thriving, and growth. Revenge is the desire to destroy the enemy’s nurture, thriving, and growth. People in privilege often perceive survival as revenge–an oppressed person defending their thriving is not an assault on your thriving. (And this is the fundamental message we must communicate to neo-Nazis). Can you extend forgiveness-with-survival to neo-Nazis? No, because they are not repentant. But with those who are repentant, you can extend forgiveness-with-survival?

So Can You Love the Enemy Who is Trying to Kill You?

There are no easy answers–that was clear from the moment we left Kant for situational ethics. Instead, the conclusion we come to is this: you cannot police how someone else loves their enemy. White people, people in privilege, do not get to dictate the terms of enemy-loving. What they can do is confess role-relational morality over and over, and over and over. People in privilege can confess loudly that all ethics is situational ethics, that loving your enemy is a slippery, ever-changing, guessing, crazy-making process–but a worthwhile, vital, deeply faithful one.

Another way to think about allyship.

And if do want to post something about Loving Your Enemy: specify which type of love you mean.

Thank you for this provoking my thinking here. At the community center where I volunteer, I asked a guy to carry something for me (I’m an old, white male with a bad back), but he “rudely” ignored me. I wonder now if you have given me an understanding of his actions.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this story! It takes a lot of courage to revisit your assumptions.

LikeLike

Many thought-provoking observations here; thank you. And your last paragraph made me smile, watching you try to combine the dogma of race-based analysis with the gospel of Messiah Jesus.

LikeLike

Dear Ms. Watson,

I think that are on the wrong track.

1. There’s an individualist misunderstanding of ethics (ethics is a decision between me and my god or my conscience) which has been popularized by people like Kant and you haven’t really overcome it. But ethics is not “What am I to do?”, but “How will we treat each other?” The goal of ethics are mutual promises and agreements: living up to forthcoming agreements or keeping agreed agreements.

2. That’s why “situational ethics” is wrong. Mutual promises and agreements are always about general rules of conduct. A general rule can imply situational differences and say: “Under these conditions we shall behave so, under those different conditions otherwise”. But: “I will treat you so-and-so, but depending on the situation I reserve my right to do whatever” – no, this is no promise at all and unapt to become a mutual agreement.

3. Because of your individualist misapprehension you have overlooked the central rule of Christian ethics. It’s Matth. 7,12: “So whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them!” Well, “Love thy enemy” does sound more noble, but as your text shows, it allows for an indefinite lot of reservations. Matth. 7,12 is more dry and precise and therefore much more demanding.

LikeLike