The logic goes like this: Christians like coffee (and tea). Non-Christians like coffee (and tea). Pastors really like coffee (and tea). Why don’t we unite around the things we like and use coffee to grow our community? And thus, a whole generation of missiologists and pastors came up with a really, really good theory–in theory.

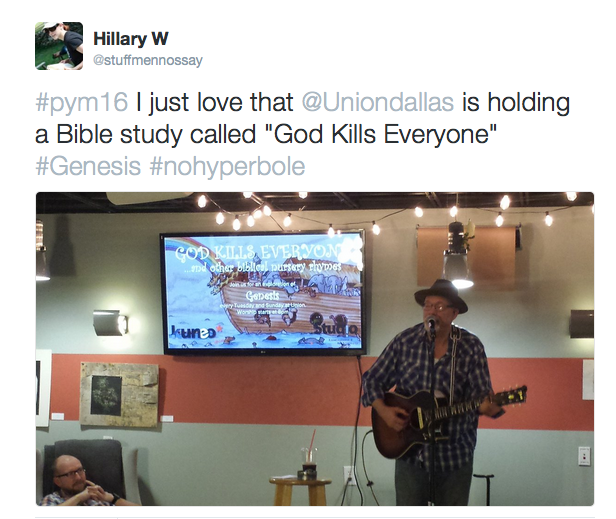

Coffeeshop ministries are trendy. Especially in the Methodist church, where church plants seem to go hand-in-hand with brand management, but it’s true in many corners of American Christianity. In February, I was at the Progressive Youth Ministry Conference in Dallas where–surprise–an evening event was held at Union, a charming Methodist-funded dual-purpose storefront with the tagline “coffee. community.cause.” and a Tuesday evening worship service that means “kiss” in ancient Greek.

The space was cozy, tucked into one of the few walkable neighborhoods in sprawling Dallas. Amateurish, friendly art adorned the walls. The decor was somewhere between Dove’s Real Beauty and Starbucks’ Race Together, depending on your aesthetic orientation. On every wall, screens rotated a mosaic of self-congratulation, reminding you of all the good you were doing by purchasing a cup of coffee.

Don’t you want to be GENEROUS, though?

And that’s just it: the drinks were expensive. I came in with three other pastors, all of whom declined to purchase. And Union was a successful church-coffee combo. The conference organizer introduced the location, “You know all your friends who say they’re going to plant a coffeeshop ministry and you see them five years later and they say, ‘Yeah, that didn’t work out’? Well, here’s the guy who worked it out.”

Later, another conference attendee who knew the place said, “Yes, it’s worked so far. But they’re not sure they can sustain it.”

The more I consider it, the more I am convinced that coffeeshop ministry is a good intention whose gallons of pour-over are paving the road to hell. Metaphorically, at least. Coffeeshops are trumpeted as a way to reach Millennials, which Union is doing fairly effectively. There’s the inherent flaw of the bait-and-switch marketing in a generation that craves authenticity: “You wanted a coffeeshop? Surprise! That’s not what you really want. You want more friends and a sense of belonging.”

The coffeeshop ministry challenge: finding the right balance of hospitality and flippant religiosity to pique your religious appetite.

But there’s a more fundamental conflict of interest in the coffeeshop model. The premise of church planting is that people are unhappy with the story their lives are telling, and inviting them into the story of Christ will fill them with purpose, joy, and relationships. But coffeeshops, more than most other institutions of capitalism, have a narrative. Coffeeshop people–the die-hard regulars you depend on–they already have a narrative in which the coffeeshop is the catalyst that facilitates meaning, joy, and relationships. Heaping Jesus on top of that seems like superfluous philosophical speculation.

Coffeeshops are also the battleground of the new cultural capitalism. If Millennials are bad for church, they’re worse for capitalism. They’re cheap-ass, overeducated, indebted artistic types who don’t own cars and reject Christmas presents because they want “experiences not goods.” These are the people who would rather torrent a film with Chinese subtitles than walk the three blocks to Redbox and pay for a $2 movie. Millennials don’t grow the economy. They want identity, not material goods. That’s disastrous on a capitalist consumer economy.

But thank the god of capitalism for Starbucks. Starbucks has set the definition of coffeeshop as an inherently ethical proposition–you’re not a homey Third Space until your coffee buys more than a cup. Coffeeshop is now synonymous with the culture of local, fair-trade ethical economics. And local, fair-trade economics requires us to buy into the idea of ethical consumerism. Whatever damage we cause in the course of consuming–environmental or human–can be rectified by the consumption itself. Or, as Slavoj Zizek says, “You don’t just buy the coffee, you buy in the very consumerist act, you buy your redemption from being only a consumerist.”

Coffeeshops, in cultural symbolism, are a tacit endorsement of cultural capitalism, of redemption through the system itself, which is nothing if not antithetical to the message of Christ. A system can redeem itself only by an act within the system that undermines the system itself–resurrection where there was supposed to be death. That is, redemption happens when real change destabilizes the system and constructs a new one.

Coffeeshop ministry is an ode to the $8 minimum wage; to intercontinental imported luxury goods; to consumption and community and inherently redemptive without a broader narrative of redemption. I love cofeeshops. Coffeeshops do have a very real cultural capital and facilitate many positives. But the church’s endorsement of coffee ministry is akin to baptizing Constantine and calling Rome a Christian empire. It inherently limits our capacity to speak into the injustice of minimum wage, freelance economy, and gentrification.

Back in Dallas, Union advertises food drives and donates 10% of each coffee to charity. They even make and donate superhero capes to hospitalized children. At Union, as Jay Z would say, your mere existence is charity. Your presence is one giant indulgence–so who needs God, when the churchshop has already made you ethical without God? Union uses cultural capitalism as a means to God–it uses the self-congratulatory cultural capitalism to say, “See? Isn’t Jesus easy?”

Union does change lives, and has a series of video testimonies to prove it. I don’t want to condemn it outright because it is working as best it can in its own corner. Union is genuinely trying to experiment with new forms of Christian community. That’s laudable and creative and the church needs that creativity. But it still seems, in their model, that Christianity plays to upper-middle-class Millennial guilt and assuages it. And so it seems to miss the central premise of the gospel–doing good is not corporate penance, it is identity.

I don’t drink coffee. Or tea. Medical reasons mostly, but I hadn’t really acquired the test by the time those reasons kicked in, either. Occasionally these kinds of churches (and church events) offer me hot chocolate, but a lot of the time there isn’t even water. I’ve been to several church events where I was really thirsty but I was out of luck because they had just assumed everybody would be happy with coffee as the only option. This is a shallow point compared to your post, but seriously, it’s annoying when churches are trying so hard to be cool that there’s no room for the rest of us who aren’t so cool.

LikeLike

Hi, thanks for a most interesting discussion. But after reading it, and visiting the Union site, I’m left thinking you are being too critical. I don’t know anything more than what I’ve read there, but it seems like it’s a better attempt than most to do something positive for a certain target “audience”. I’m not sure I understand why you are negative. Yes, they’re appealing to rich middle class millennials, but that’s who lives where they are I guess. Yes, I too am a little suspicious of something that is mega trendy, but better that than mega boring or mega irrelevant.

So I don’t really understand your implied balance sheet of the good and the not-so-good. Nevertheless, I appreciate your review and website, thanks.

LikeLike

Thanks! I am probably being more critical than I need to be. I don’t have any personal grudge against Union. But my most relevant concern to Union is that their model is undercutting itself–when your whole cafe is structured around “doing good,” why have a church? If you can live ethically without God, how does Union make the case for God? Or for any theological/spiritual dimension to life? I had a very positive experience at Union (in the coffeeshop format, not the church format). But I think the model will have to change–and the division between church and business will probably have to become sharper in the process.

LikeLike

That’s an interesting issue, which I didn’t understand clearly originally. I’d be interested to discuss further if you were willing. Here are a few questions/thoughts:

1. Do they say people can be good without God? Do you think people can’t be good without God? What level of “good” are you using? I’m less troubled by that idea than you seem to be.

2. Is being good the only, or main, reason why people should follow Jesus? I’m inclined to think that if we find we have an ethical belief that leads to action in common with unbelievers, that is a good thing. We can work together for good with them, be friends, pray for them. Eventually I would hope they’d want to follow Jesus because they believe, like us, that he is truly the king of the universe, that he can empower, guide, lead and forgive us, and we need all those things.

3. Why do you think the church needs to be more of a division between church and business? I feel that if we allow the business and the fellowship that happens there to be the people of God, that is enough.

I’d be interested in your further ideas – after all, I haven’t been there. Thanks.

LikeLike

Pingback: An Odd Bunch of Believers: The Sent Conference and Courage Beyond Institution | gathering the stones